I saw in my glass a picture, that if I could transmit to you, & fix it in all the softness of its living colours, would fairly sell for a thousand pounds. This is the sweetest scene I can yet discover in point of pastoral beauty.Thomas Gray (1717-1776), writing of a view in a Claude glass.

*

The Claude mirror, a landscape-viewing device, is a pre-photographic optical instrument that was widely used in the 18th and 19th centuries. Its popularity is closely linked to the rise of the Picturesque Movement. It was named after its ability to transform a landscape view into something reminiscent of a painting by 17th-century French artist Claude Lorraine. These small, black, convex mirrors, usually sized for the hand, were extensively used by artists and tourists to contemplate, reconfigure and record landscape. They were wielded on picturesque tours of Britain, the Continent and North America. In areas such as the Wye Valley or the Lake District, tourists would halt at proscribed Viewing Stations (maps and mirrors available at opticians, stationers, art suppliers and, later in the period, tourist stops), turn their backs to the scene, hold up a Claude mirror, and look at the framed and transformed view. The distorted perspective, altered colour saturation and compressed tonal values of the reflection resulted in a loss of detail (especially in the shadows), but an overall unification of form and line. The Claude mirror essentially edited a natural scene, making its scale and diversity manageable, throwing its picturesque qualities into relief and - crucially - making it much easier to draw and record.A. McKay and C.S. Matheson, The Transient Glass: The Claude Mirror and the Picturesque.

*

The glass was a convex, oval mirror shaded so as to impart to the scenery the painter's brownish tints. They aimed it over their shoulder and looked into it for the right sort of picturesque view, in effect looking at nature backwards, in a dark glass. They analyzed a prospect for its picturesque qualities—for the correct placement of trees, the height and steepness of its mountains, and the form of its lakes. Even without a Claude glass, they criticized natural views for their lack of some picturesque quality. Perhaps a tree might be misplaced, or a stream not rugged enough. Picturesque artists felt no compunction in altering a landscape to suit their ideas of what should be, rather than painting what was.Carol and Richard Buchanan, Wordsworth's Gardens.

*

The mid- and late-eighteenth-century development of sensitiveness to nature and one's physical surroundings was at least partly owing not to the attractiveness of nature itself but to the rise of interest in landscape painting, specifically the works of two seventeenth-century schools, Dutch and Italian, that favored wide and deep prospects, rugged scenery, a blurring mistiness in the distance, classical and medieval ruins, and frequently, in the foreground, the presence of shepherds and other rustic figures. The best-known painters of the Italian school — Claude Lorrain, Nicolas Poussin, and Salvator Rosa — were collected by the wealthy but also were made popularly available in sets of engravings with titles like Beauties of Claude Lorrain. The eighteenth-century vogue for these artists caused a revolution in landscape gardening, whereby formal arrays of trees, shrubs, paths, and ornaments in geometrical patterns were replaced by "landscape" gardens designed to look, from a specified vantage point, like a scene by Claude or Poussin. Walls and fences were hidden in ditches so as not to obstruct the long view; old ruins were created, Disneylike, on the spot, and servants were engaged to pose as farmers, shepherds, and hermits. The predictable next step was for people to venture out in search of landscapes in nature itself — first with an optical device called a "Claude glass," a tinted convex mirror in which one could compose, over one's shoulder, scenes in nature that resembled paintings by Claude, and then, leaving the mirror behind, confront nature face to face.The Norton Anthology of English Literature.

*

Image: Claude Glass, made 1775-1780.

Related:

Arnaud Maillet: The Claude Glass: Use and Meaning of the Black Mirror in Western Art

Andrew Douglas Underwood: The Claude Glass

Emma Weislander: Black Mirror

Barnaby Hosking: Claude Mirror Sun

Claude glasses in the collection of the U.K. National Maritime Museum

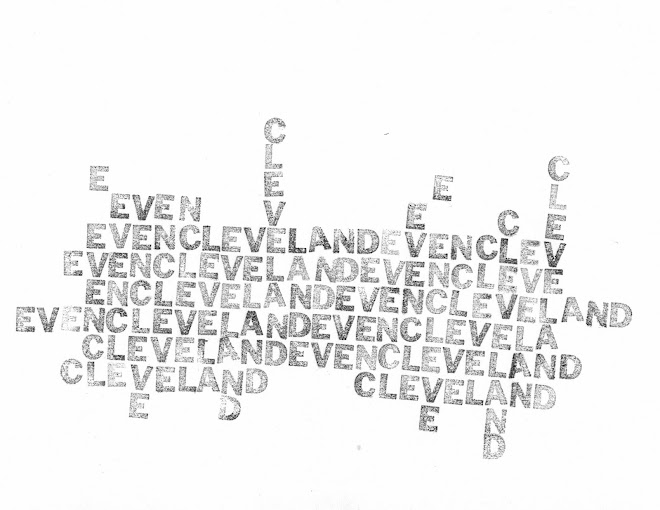

This also came to mind.

Discovered thanks to kottke. More here + here.